Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a protein concentrated on the surface of prostate cancer cells with limited expression on other locations in the body. As covered previously on the blog, PSMA can be exploited for both imaging and treatment utilizing either large monoclonal antibodies or small molecule targeting agents.

PSMA-targeting entails attaching a radionuclide (a particle that gives off radiation) to an antibody or small molecule designed to recognize and bind to PSMA. Research into PSMA-targeting has led to promising investigational treatments and transformed how we can detect prostate cancer. In December 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave limited approval for 68Ga-PSMA11 PET scans for patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer and patients with rising prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels following radiation or surgery. This form of FDA approval allowed for specific facilities in California to use this agent outside of the clinical trial environment. 68Ga-PSMA PET, which has been used elsewhere in the world without strict regulation, allows doctors to better detect recurrent and hidden prostate cancer and consequently, to choose the best type of therapy for each patient.

Weill Cornell has a dedicated team of physicians that study and interpret 68Ga-PSMA PET imaging. Numerous studies have demonstrated that 68Ga-PSMA PET is more effective than traditional scans (such as CT or MRI) in finding metastatic prostate cancer (sites where the cancer has spread elsewhere, including microscopically) and in a small head-to-head study was also better than 18F-fluciclovine (Axumin) PET/CT. There are a number of ongoing trials at Weill Cornell and elsewhere evaluating the use of PSMA targeted imaging, which currently remain the only way to obtain PSMA PET outside of California, with additional approvals of PSMA PET agents expected in the first half of 2021.

At the 2021 Genitourinary (GU) Cancers Symposium, researchers presented a head-to-head comparison of 68Ga-PSMA11 PET vs. MRI in detecting and staging localized prostate cancer (disease mainly confined within the prostate) in 74 patients. The two imaging methods had similar performance, with PSMA PET a little better for tumors outside of the prostate and MRI better for identifying tumor invasion of structures adjacent to the prostate. It may be that the combination of both methods will further enhance prostate cancer staging and a study is currently being done at WCM to evaluate this combination.

Additionally, a number of studies on PSMA-therapeutics were presented at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. There is an ongoing trial investigating PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy (PSMA-TRT) with radioactive iodine in combination with the prostate cancer drug enzalutamide; radioactive iodine (Iodine-131) is conjugated to the small molecule 1095. An initial study of 10 patients receiving PSMA-directed/TGFβ-insensitive CAR-T cells (immune cells that have been engineered to recognize PSMA) demonstrated safety and efficacy. In this study, 60% of patients experienced PSA decline, ranging from 11.6 to 98.3%, and post-treatment biopsies demonstrated CAR-T cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, there is an ongoing clinical trial of a bispecific antibody (REGN5678) that connects PSMA with immune cells, which can subsequently destroy the cancer cell; this bispecific antibody is combined with a medication called cemiplimab that further strengthens the body’s immune response.

There are multiple agents utilizing PSMA small molecules to carry the beta-emitting radionuclide lutetium-177 (177Lu) to PSMA-positive areas in the body (mostly areas of cancer spread). Updated results of a prospective head-to-head comparison of 177Lu-PSMA-617 vs. cabazitaxel (a type of chemotherapy) in 200 patients with advanced prostate cancer were presented at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. In the data initially shared at ASCO 2020, the main objective was met, with more patients receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 having PSA response compared to cabazitaxel chemotherapy. In the updated report, patients receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 had longer disease control (both by PSA measurements and scans), with fewer side effects and more improvements in quality-of-life. Recently, VISION, the multicenter phase III clinical trial comparing 177Lu-PSMA-617 + standard of care against standard of care alone in patients with advanced metastatic prostate cancer, has shown that patients receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 lived longer and had longer disease control. Full results will be presented at an upcoming research conference, and we hope that this study leads to FDA approval in the future.

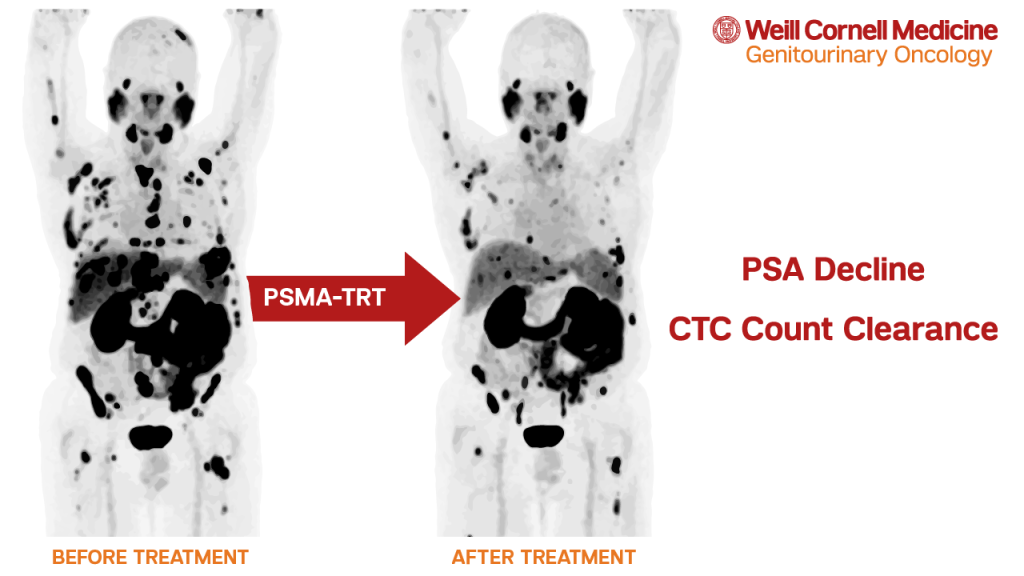

In general, tumors spread to other parts of the body via the bloodstream. The ability to capture these tumor cells, called circulating tumor cells (CTCs), has led to significant prognostic information along with the ability to study the cells as part of a “liquid biopsy”. When a number of different types of therapy is able to decrease or clear CTCs from the circulation, those therapies generally make patients live longer.

Weill Cornell researchers examined several sequential prospective clinical trials utilizing various PSMA-TRT agents. In an analysis of 116 patients, 70% treated with PSMA-TRT and with CTC counts before and after therapy had a decline in CTC counts. Some PSMA-targeting agents (i.e. the carrier molecules) may have anti-cancer effects on their own. While it appears that agents labeled with radioactive particles are more effective, some patients treated with anti-PSMA antibody J591 alone had control of CTC counts.

Alpha and beta-emitting radionuclides have different properties. In 2020, we presented preliminary information at ASCO that a single dose of the potent alpha-emitter actinium-225 (225Ac) linked to antibody J591 (225Ac-J591) was safe, and despite lack of selection of patients with PSMA PET and prior 177Lu-PSMA therapy in the majority, 60% had PSA decline.

At the 2021 GU Cancers Symposium, investigators presented the design of WCM’s ongoing clinical trial investigating either fractionated (2) or multiple-dose (1-4 doses) of 225Ac-J591. This study (NCT04506567) is one of many PSMA-targeted therapeutic clinical trials open at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.