Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT), or hormonal therapy, is widely used in the treatment of metastatic and locally advanced prostate cancer, as most prostate cancer cells rely on testosterone to grow. Suppressing the testosterone hormone can cut off a fuel source for the prostate cancer. While ADT is a highly effective treatment and can be administered before, after or during radiation therapy, it is not without side effects. Some of the most common side effects of ADT are hot flashes and night sweats. Almost 80% of patients with prostate cancer experience hot flashes during or after treatment with ADT.

Hot flashes are sudden sensations of warmth, typically in the upper body in the face, neck, and chest areas. This sensation is often accompanied by sweating and flushing. Hot flashes can last seconds or as long as 20 minutes. They can also be associated with sleep disturbance, depressed mood, anxiety, and cognitive impairment. Hot flashes combined with sweating while sleeping are called night sweats. Night sweats because of ADT should not require patients to change their sheets daily due to drenching. Drenching is unlikely a side effect of ADT and should be discussed with care team members as this may signal that something else is going on. Experiencing hot flashes and night sweats can decrease quality of life in men with prostate cancer and can lead to premature discontinuation of treatment, even if the therapy is working to keep the cancer at bay.

There are pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions available to control hot flash symptoms and reduce the frequency of the sensations. These interventions include physical activities, behavioral therapies, device-based and pharmacologic (drug) interventions, as well as natural health products. It should be noted that some interventions, such as venlafaxine, which are a mainstay for treatment of hot flashes in women with postmenopausal hot flashes or hot flashes associated with breast cancer treatment have been proven to be ineffective for patients with prostate cancer. Some lifestyle and behavioral modifications that can help reduce the impact of hot flashes include avoiding caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco, as well as increasing exercise and physical activity.

In addition, the below methods for managing hot flashes were recently presented as part of new research shared at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting in June 2024.

- MANCAN2: Results from this multicenter clinical trial evaluating cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to help patients with prostate cancer who are receiving ADT to manage hot flash and night sweat symptoms showed that a 4-week CBT program during ADT treatment reduced the impact of hot flashes and night sweats and resulting anxiety and depression for six weeks. The improvement, however, was not seen when looking further out to the 6-month mark. This study warrants further research to investigate the role of CBT in managing hot flashes and whether this benefit can be prolonged.

- Alliance A222001: This randomized clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of Oxybutynin, a drug that blocks the action of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, to improve hot flashes. Study authors concluded that twice-daily oxybutynin improved hot flash symptoms and reduced the frequency of hot flashes altogether compared to a placebo at the primary endpoint of 6 weeks. Oxybutynin, which was initially developed to treat urinary incontinence, did not have many severe side effects reported in the study. Since the drug has been used by many for urinary reasons, it is known that a common side effect is dry mouth, which occurred to a significant (moderately severe) degree in about 9% of patients taking oxybutynin and 8% of patients taking placebo. This drug is not FDA approved for the treatment of hot flashes.

Hot flashes were discussed widely at this year’s ASCO meeting, including in a session called, “Living Your Best Life on Treatment.” This important topic underscores the need to continue to discuss and develop interventions with the potential to improve quality of life for patients undergoing prostate cancer treatment. It is ultimately through new research and updated information that clinicians and patients with prostate cancer can work together to better manage, reduce or eliminate hot flashes.

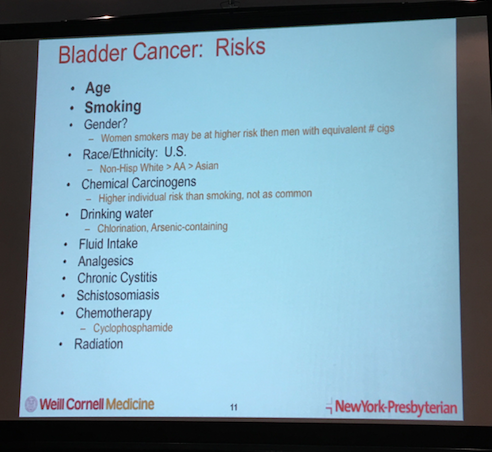

Dr. Tagawa highlighted the importance of using a uniform method for developing and testing biomarkers in bladder cancer, a disease with a high incidence of recurrence and expensive clinical surveillance. He also pointed out that most bladder cancers are of a type called transitional cell, affecting the same kinds of cells (transitional cells) that are usually the cancerous cells responsible for renal pelvis, ureter as well as kidney cancers. Dr. Tagawa described the four main phases of bladder cancer.

Dr. Tagawa highlighted the importance of using a uniform method for developing and testing biomarkers in bladder cancer, a disease with a high incidence of recurrence and expensive clinical surveillance. He also pointed out that most bladder cancers are of a type called transitional cell, affecting the same kinds of cells (transitional cells) that are usually the cancerous cells responsible for renal pelvis, ureter as well as kidney cancers. Dr. Tagawa described the four main phases of bladder cancer.