For men with metastatic prostate cancer that grows despite hormonal therapy (also referred to as castration-resistant prostate cancer), chemotherapy has been a mainstay. The class of chemotherapy that has consistently proved to improve survival for men with advanced prostate cancer is called “taxanes.”

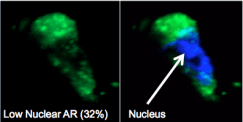

Taxanes target microtubules, which are structures in cells that are involved in cell division, as well as the trafficking of important proteins. In prostate cancer, one of the main ways taxane chemotherapy works to kill the cancer cells involves blocking the movement of the androgen receptor (AR) along the microtubule “tracks” towards the cell nucleus, a mechanism we discovered here at Weill Cornell Medicine.

There are two taxanes FDA-approved to treat prostate cancer, docetaxel (brand name: Taxotere) and cabazitazel (brand name: Jevtana). While the drugs are similar, men whose tumors have grown despite taking one drug often respond to the other. The challenge for oncologists has been pinpointing when exactly to switch treatments.

Dr. Scott Tagawa presented exciting results from a phase II clinical trial at the 2016 American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting demonstrating the power of this treatment switch, and when to make the switch.

Dr. Scott Tagawa presented exciting results from a phase II clinical trial at the 2016 American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting demonstrating the power of this treatment switch, and when to make the switch.

This research came to be because we thought that we might be able to increase the number of men who respond to taxane chemotherapy with an early assessment and by changing the drug for those who have a sub-optimal response. Simply put, those with no response or only an initial minor response had their drug changed at a much earlier time point then standard practice. This resulted in a higher response rate for the patients in the study.

In addition, it’s very exciting that we can examine cancer cells from a simple blood test, a process also referred to as collecting circulating tumor cells or CTCs. This allows us to assess the ability of a drug to target the pathway in real time and to tell us whether there is a positive tumor response or resistance.

These circulating tumor cells provide an opportunity for real-time molecular analysis of taxane chemotherapy and at Weill Cornell Medicine we’ve pioneered a way to examine the AR pathway with a simple blood test.

To do this we use an extremely specialized technology that captures the very small fragments or rare circulating tumor cells on a “chip.” From this chip we are able to determine which cells are responding to treatment.

In cancer care, we are always trying to maximize treatment response rates by targeting the right cells at the right time. This promising precision medicine approach offers us one more tool to better personalize treatment and improve outcomes.